![]()

1 Introduction

2 History - The Area

3 History - The House

4 Construction - Front Elevation

5 Construction - Rear Elevation

6 Construction - Main Roof

7 Construction - Ground Floor

8 Construction - Upper Floor

9 Layout - Ground Floor

10 Layout - Upper Floor

11 Layout - Roof

12 Introduction to Reports

13 Home Condition Report

14 Valuation Report

15 Home Buyer's Report

16 Building Survey Report

17 Home Condition Report

18 Standards of Practice

19 Allied Surveyors

32 Frederick Street is a real property (if not a real address) in Bristol. It's located about 4 miles, or so, from the city centre and was built about 1900. To help students and junior practitioners understand the various types of pre-acquisition surveys we asked a local chartered surveyor to carry out a number of surveys including:

The details of these surveys can be found in pages 7 to 9.

Over the last hundred years or so there have been a number of changes in construction materials and techniques. Some of these have been dramatic, for example, the introduction of electrical wiring systems in the 1920s. Others have been a steady process of evolution, for example, the shift from lime plasters to gypsum plasters and gypsum dry-lining systems. To help people understand the original construction of 32 Frederick Street, and to help them understand some of the changes that have occurred over the last hundred years or so, we have produced a series of web pages showing the construction of the main building elements. We have also produced floor plans with a number of 'hot spots' showing photographs and typical construction details. Finally, we have produced a short video containing general comments and observations from the surveyor.

We have also included a section on Frederick Street's history and original development. This has been a fascinating piece of research and shows the wealth of information that's available on older buildings - if you know where to look. Most of the information came from local authors, Bristol Central Library and the local Public Record Office.

All the material on this web site is protected by copyright. The web site must not be copied or distributed to other individuals or organisations. Registered students may download the reports, drawings, text, and video clips.

Discovering the history of a house can be very rewarding and will also provide useful information, especially with regards to its original construction and materials. Historical research can often show where alterations have been made to a building or give clues to why defects have occurred. It may be necessary to do some historical research into a building as part of a survey.

|

32 Frederick Street was built in 1903 - the beginning of the Edwardian period. This period was an active time for private house builders across the country; in fact, the same year saw a national peak in house building. Largely this was speculative building to meet demands for new rented housing for the rising urban population. The original application (left) to build No 32 was submitted to the Bristol Urban Sanitary Authority on the 26th February by a local builder Mr Richard Davies, who planned to construct a total of four new houses on the street. Most of the houses on Frederick Street had been built earlier just before the turn of the century (right-hand plan shows houses built in 1899), but it was in 1903 that Mr Davies snapped up his building plots, one of which became No 32. The house was fairly modest in size but well-built and most likely would have been a respectable address for the working classes. |

|

|

|

A good starting point for researching the history of a house and its

locality is at the

local Record Office. Sources might include original Building Plans,

Highway Notices and old Ordnance Survey maps for the area. For Frederick

Street we were able to access these records at Bristol's City Record

Office (www.bristol-city.gov.uk/recordoffice). Staff at the Record

Office are usually able to give good advice on how to start your search if

you visit. It is worth taking a digital camera to record any findings.

Other good sources of information are local libraries and regional

newspaper offices where often you can

search the local history section for books, maps or old photographs.

|

|

|

|

The records show that the Street itself has officially existed since 1900, having been “Sewered, Levelled, Paved, Flagged, Channelled, Metalled, and made good, and provided with proper means of lighting”, (see original Highway Notice 1900 right and left) the Bristol Urban Sanitary Authority were satisfied that the street be officially recognised within the Parish of Horfield. The area of Horfield where Frederick Street is located is much older. First mentioned as 'Horefelle' in the Doomsday Book, by 1778 it was recorded to have a population of 125, most dwellings situated around the Church and the Common which extended for 34 acres, some of which is still there today. The area was notorious for its forest, called ‘Horwood’ which was said to shut out all communication with surrounding villages. There existed a long tradition of belief that it was not safe to pass that way singly at night and travellers would wait to form parties before venturing through the forest! (Amesbury et al, 1997). |

|

|

|

As late as the 1880’s Horfield was still largely a rural village and a suburb of Bristol, described as a 'valley with gorse and furze, fields rich with cowslips and bluebells, streams and cattle' (Winstone, 1977). An early OS map of 1881 (left) shows Horfield Common surrounded by fields, dotted with farms. Mass building was underway by the late 19th century and importantly by 1880 the stream tram had reached Horfield bringing a transport connection between residents and their work in the City. In 1885 Bristol’s boundaries were extended and Horfield was including in this expansion. By the turn of the century Frederick Street was taking shape, built on the old Beehive Estate. The OS map of 1903 (right) shows the encroaching streets (Frederick Street circled in red) impinging on the fields and pastures of the Parish. |

|

|

The period when Frederick Street was built was a time of changes in the economics of the housing market in the country, the real cost of housing fell, materials became cheaper and more standardised. There was a boom in speculative house building (photo left shows houses going up in a nearby street in 1903) and the self-contained terrace house, like Frederick Street, dominated working-class housing in England by the turn of the century. Described as a ‘through house with back addition’ the layout was common across Bristol especially in other working-class areas of housing such as Bedminster and Easton. The later OS map of 1948 (right) shows the growth in the area, the Common is still visible but has been largely surrounded by Victorian streets. |

|

|

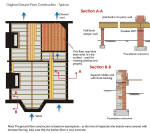

32 Frederick Street, like the neighbouring houses on the street, displays an early Edwardian architectural influence. It is a two storey mid terrace built from brick and stone walls with a timber and tiled roof with terracotta mouldings (original section plan shown right). The original plans show drainage was by means of 4″ and 6″ glazed stoneware socketted pipes jointed in cement and connected to the existing sewer at rear. The original plans submitted by the builder show the four vacant building plots and detailed section drawing. |

|

|

The internal plans (left) show the proposed layout of the house. A hallway (like the one below from the same period) leads to the parlour at the front with large bay window and fireplace, kitchen at the back with range and an adjoining scullery with back door. Upstairs there are three bedrooms, all with windows and fireplaces. The parlour (or ‘front’ or ‘best’ room) was an important room to most working-class families, a shrine to respectability and domesticity it was often a setting for special occasions. The provision of a scullery meant the sink and copper (previously in the kitchen) could be moved to a utility area. Cooking and washing of clothes and dishes could now take place in the scullery and the kitchen could be retained as a place for eating and general living. Cooking would have mostly been done on a range in the kitchen, like the one on the right, which is shown in poor condition with original gas lamp above. |

|

|

The photos on the left and right show an early interior of a scullery with ceramic sink and a copper (possibly coal fired) in a brick built surround with a wooden lid, used to heat water for washing clothes or bathing. In the space outside the back of the house are the coal store and W.C. This private patch of territory marked an improvement in working-class housing standards where each house could accommodate an individual privy, compared with conditions in the mid-century where broken and overflowing cesspools often shared by occupants of a dozen or more houses were common. However, still in 1903 it was still very unusual for house builders to risk locating the water closet inside the house itself, so as with 32 Frederick Street it was located in the back yard. |

|

|

Our house on Frederick Street is the type that would have been rented by the skilled or better-paid workers. It was very uncommon for people to own their own homes at the beginning of the century so most people rented from private landlords. Information from the 1905 Wrights Bristol Directory and the 1901 Census (available at the Record Office or online) tells us that our house was first occupied by Mr Edward Webber, a 27 year old Grocers Assistant who lived with his wife Eleanor. Both were local people having been born in the Parish of Horfield. The Webber’s neighbours included John C. Powell, a Carpenter and Joiner and his wife Clara, and Tom Waters, a Clothiers Assistant who shared the adjoining three bedroom house with his wife Maud and four children, Polly, Jan, Reg and William. |

|

|

Local history books and wider literature on this period

of history can be useful in understanding the background of when and why

a house was built.

Sources for Frederick Street:

All images © Bristol's City Record Office except where indicated |

||

The construction of 32 Frederic Street is typical of hundreds of thousands of late-Victorian terraced houses up and down the country. The style and building materials of the elevations may differ across the UK but these differences tend to be cosmetic. Most houses like this were built in 6 months or so and would sell (outside London) for about £300. They were mostly built by private speculators for rent.

|

The front elevation is constructed of stone, probably with a brick backing. The thickness of the front wall is about 450mm. This is thicker than one would normally expect but might reflect the nature of the stone (it was probably quite difficult to cut accurately). This house was built in about 1900 or so. It would have been subject to local by-laws and the Public Health Acts. Towards the end of the century legislation set out minimum foundation depths, wall thicknesses and the need for damp proof courses. However, don't assume anything - this house may have a shallow concrete, stone of brick foundation; it may have no foundation at all. Click here to see some examples of late Victorian external wall sections. Finally, remember that even if there is evidence of a DPC it does not mean it's working properly. |

|

|

Architectural terracotta was very popular during the late Victorian period. It was hard, fireproof, easy to wash (especially in its glazed form - faiance) and resisted damp and pollution. It was available in a range of colours including buff yellow, pale cream, red and brown. It was perfect for providing decorative relief to buildings - usually in a mish-mash of gothic and classical styles. On this building there are column capitals on the door surround and window mullions, a pediment and a key-stone over the door, a dentilled cornice at the eaves, and lots of flower motifs (most of them below the bay). The party wall is decorated with a terracotta interpretation of 'V' jointed ashlar. See www.buildingconservation.com for a very good article on Defects and Repairs to Terracotta. |

|

|

In some parts of the country the party walls of Victorian and Edwardian terraced houses extend beyond the roof. These are known as parapet walls. They can be brick or stone, sometimes with a rendered finish. These projecting walls provided a fire break and an architectural detail. The party wall is probably one-brick thick and is most likely to be built in English Garden Wall bond -normally with a row of headers every 4th or 6th course. The sloping top is normally protected with a clay or stone coping - the bottom coping is mechanically fixed in position to stop the copings sliding off the roof. On some houses (including this one) the bottom end of the parapet wall is level so the end copings can be laid flat. |

|

|

During the Victorian period, and indeed until the 1920s, most house were built with sliding sash windows. Some houses had sashes divided (with glazing bars) into small panes but most had sashes with just one or two panes of glass. Sash windows fell out of popularity in the 1930s when they were largely replaced by side-hung casement windows, usually with top-hung lights. The windows at the front of Frederic Street are aluminium - they have top hung lights but the main part of the window is fixed. These windows were cheap, reasonably durable, but not much help as a means of escape. They are fixed in wooden frames - the original sash window box frames. |

|

|

Bays provide a bit of extra space, better daylight to a room; they are also a decorative feature. On Frederic Street the bay is single storey; in some houses the bay is two storey. The pitched roof over this particular bay matches most in the street so it may be original although many of these bays were designed with low parapets and a lead flat roof. Over the years these often gave rise to drainage problems - usually because of leaks around the outlet. The bay here is covered with plain clay tiles; sheet-lead covers each hip (the external angle). |

|

|

Originally, the front walls would have been tuck-pointed (right). This was a slow process and it's rarely used nowadays. Tuck pointing was an attempt to fool the viewer into thinking the wall was built from finely cut stone or very accurately made bricks - at the time the best work had very thin mortar joints. Tuck pointing is in two parts, a lime bedding mortar often containing aggregates to match the colour of the bricks or stonework, and a thin ribbon of lime pointing to finish the joint. From a distance the wall appears to be finely jointed. The ribbon pointing (left) has probably been done (using cement mortar) some time in the last 30 years or so. It's slow, expensive work; not particularly durable and certainly not traditional. |

|

|

In Bristol, as in many parts of the UK, most late nineteenth century terraced houses were built with raised timber (suspended floors). A separate page describes these in more detail and provides a typical floor plan showing joist and board layout. The durability of these floors depends, in part, on good ventilation. In practice you will find that many of these floors do not contain adequate ventilation; this is either due to lack of original provision, or due to blocked vents. At Frederick Street the vents are actually incorporated in the terracotta flowers (right) below the bay. Originally there would probably have been a vent below the front door - there is no sign of this now. |

|

The rear elevation is slightly unusual in that there is a single storey, full width extension, probably built in the 1970s. Originally the house probably had a small lean-to extension at the back of the house containing a WC. It is unlikely that the house would have been built with a separate bathroom - there was a probably a tin bath (filled and emptied by hand) in the scullery (now the kitchen).

|

The main house wall is 1 brick thick, probably in English Garden Wall bond. When the render is removed from these properties it's sometimes astonishing how few headers there are binding the wall together. The original render was probably as mix of lime and sand, maybe with the addition of some cement or maybe using a hydraulic lime (both designed to give a faster and harder set). The pebble-dash render dates from the 1970s and comprises a surface dressing of stone chippings (the spar or 'dry-dash') thrown onto a sand/cement top coat. A sand/cement render coat lies below the top coat. |

|

|

The rear extension is probably cavity construction and is most likely to comprise two 100mm leaves of blockwork with a 50mm cavity. The external leaf is probably dense concrete; the internal leaf may be the same but could be some form of lightweight block. In the 1970s the maximum 'U' value for external walls was quite high - 1.70W/m2K). The 2005 figure was about 0.35W/m2K (the actual value can vary depending on the values of other elements). To form the openings it was normal practice to close the cavity at the jambs by returning the internal leaf to the outside one. The graphic shows typical construction in a brick and block cavity wall. The construction for block and block was no different. The window frame was built in as work proceeded - probably using fixing cramps as shown in the graphic. There's probably a steel, or steel and concrete, lintel at the head. It's unlikely that the cavity is closed at the sill. |

|

|

When building extensions like this it is often difficult to know how

best to connect the new structure to the existing one. It use to be accepted

practice to remove some of the bricks in the main wall and 'tooth-in' the

new work to provide a rigid connection. Unfortunately, any minor

differential foundation movement (almost inevitable) would result in

cracking. In modern construction it is more likely to provide a connection

which provides a small degree of flexibility. The wall starter system on the

left (no larger image I'm afraid) is made by Ancon. I presume that the logo

means it's NHBC approved. A similar, and not unrelated, problem is the foundation depth of the new work. What if the existing house has very shallow foundations - should the new extension be at the same depth? There is no easy answer. |

|

|

The left-hand image shows the back door. Doors like this don't offer

much protection against forced entry but they were pretty much the standard

type of back door throughout the last 50 years of the 20th century. There

are two other interesting things about this door; firstly the glass is a

safety hazard and secondly, the door frame is not a frame at all - it's

actually a door lining with a planted stop (in the form of a piece of

architrave).

The right-hand image shows the flat roof. This is likely to be a cold roof, probably with 100mm or so of insulation between the joists. The deck may be plywood but it could be chipboard. the ceiling is probably 10mm or 12.5mm plasterboard nailed to the joists. It's doubtful whether there is a vapour check. It was not clear from our brief inspection how this roof is ventilated. |

|

|

|

The drainage is not really part of the rear elevation but the inspection chamber cover is right outside the back door. This chamber was probably built at the same time as the extension - we do not know whether there was an inspection chamber on the site originally. The chamber comprises half-brick walls with a cast-iron cover. The builders never got round to completing the chamber - there's no benching. The chamber contains a central, open channel with a 'three-quarter' bend picking up a branch pipe. The cover is of a type often favoured by young marble enthusiasts. |

|

|

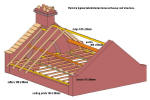

The main roof of 32 Frederick Street is a purlin roof. Until the 1950s, this was the most common type of roof construction in the UK and, in the from shown here, is ideal for small terraced, or semi-detached, houses. The roof comprises a series of sloping timbers known as rafters, supported at the bottom by a wall plate, and at the top by a ridge board. The rafters are usually 75, 100 or 125 x 50mm, depending on span; they are usually fixed at 400mm centres (16 inches). Ceiling joists support the ceiling and prevent the feet of the rafters from spreading. The roof stays in position because it's heavy (several tonnes when tiled). The roof is covered with Double Roman tiles. A series of lead (maybe zinc) soakers seal the junction against the parapet party walls. |

|

|

The ridge board helps maintain the rafters in the correct position as the roof is being built. Once the roof is complete it becomes less significant in terms of the roof's stability and rigidity. It's usually built into the gable ends, sometimes supported on corbels. At the eaves the rafters are normally notched over a wall plate bedded on top of the external walls. The ceiling ties should be well secured to the rafter feet. The insulation should run into the eaves (to prevent cold bridging around the edges of the ceiling) but should not block any ventilation. |

|

|

To help keep the rafters to a sensible size they are usually supported mid-span by a purlin. In theory it's possible to increase the span of a roof and prevent deflection by using ever increasing rafter sizes. However, the use of very deep sections is both uneconomic and also creates handling problems on site due to their weight - a purlin is therefore more practical and cheaper. A purlin is a large timber beam which generally supports the rafters mid span thus preventing deflection. The purlin spans from party wall to party wall and, besides supporting the rafters, provides lateral stability to the gable end walls (i.e. at each end of the terrace or in semi-detached and fully-detached houses)). It's usually built into the gable or party walls and, again, can also be supported on corbels. A 3D model of the whole roof at Frederick St is shown on the left. |

|

|

In very small terraced houses the purlins can easily span from party wall to party wall. However, as the width of a property increases so must the depth of the purlin if it is to be strong enough to take the load imposed on it without undue deflection. Very deep purlins, say over 250mm are expensive, difficult to obtain and difficult to handle on site. In practice it's more economic to use smaller purlins and provide intermediate support in the form of struts, built off internal loadbearing walls. In a terraced house the size of Frederick St you will normally find one pair of struts, bearing on the wall between the two main bedrooms. The struts at Frederick St are so shallow, they are almost ineffective. |

|

|

Where there is no means of supporting struts,

some other means has to be found of supporting the purlins mid span. In

larger roofs this is traditionally done by a heavy truss (left). You won't

find these in small terraced houses.

The ceiling joists which span from plate to plate are often of smaller section than rafters, and to prevent them sagging in the middle some form of intermediate support is often provided. One method is to secure the ceiling joists with a horizontal member, called a binder, and to hang the binder from the ridge. An alternative, of course, is to use joists of increased depth but this is usually a more expensive solution. At Frederick Street the joists are supported by the external walls, the internal wall between the two bedrooms, and a pair of binders. The photo (left and above) shows a binder running below the purlin. The photo on the right shows that hangers and binders are still used today, even though most roofs are built with prefabricated trussed rafters. |

|

|

In the roof void there are two main things of interest, the 'gathered' flues

(left) and the two cold water cisterns (right). The larger cistern feeds the

hot water cylinder and the smaller one the boiler - the cold water

supply is direct.

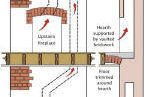

There are four fireplaces on the party wall, each served by its own flue. These are gathered into a single chimney (with four pots -8 including next door). The construction is quite complicated and there are a number of defects to look for. These are explained in much more detail on the Construction Web Site (Heating section). |

|

|

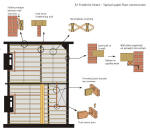

Originally, we think the floor at Frederick Street would have looked something like the graphic on the left (there is an isometric showing part of the floor on the right). Most of the floor comprises a series of joists supported by external and internal loadbearing walls and covered with floorboards. Deep joists are expensive and to reduce joist size there are usually intermediate supports known as sleeper walls. These are small walls in rough stone or brickwork built directly on the ground or on small foundations. In practice, ground-floor joists are often half the depth of those used in upper floors where, of course, such intermediate support is not possible. The room which is now the kitchen (possibly the scullery originally) probably had a solid floor - this room was designed to get wet. |

|

|

In practice timber ground floors often give rise to expensive maintenance problems due to poor design and varying standards of workmanship. Problems include:

In addition square edged boards can twist and warp. |

|

|

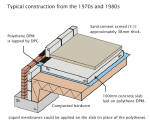

At some point in the past the timber floor appears to have been rebuilt. We could not take any ground-floor floorboards up in the main rooms because of the laminate flooring. However, using Tony's special subterranean high-resolution digital camera we managed to take a few photos of the floor below the stairs. A bigger version of the picture can be seen here. This photo appears to shows some form of concrete oversite and a reasonably recent bitumen DPC under the wall plates. Maybe this floor was rebuilt in the 1970s (when the extension was constructed). The extension floor would like something like the example on the right. The kitchen floor was probably rebuilt in the same way. |

|

|

The construction of a raised timber floor is mostly straightforward although things are a little more complex at hearths. The photo on then left shows a 1930s floor (stripped back to install insulation). You can see the chimney breast and hearth - the fireplace itself has been removed. At Frederick Street the fireplaces would have varied from room to room. The rear (left-hand) room, the living room, would originally have contained some form of range for cooking (right - a photo showing a range from about 1890). Water would have been heated in the scullery in a coal-fired copper (the corner/rear chimney stack). The front room, the parlour, would have been reserved for entertaining. |

|

|

The graphic on the left shows the upper floor construction (to some extent this is an informed guess). In summary:

|

|

|

To stop the joists from twisting or warping (and possibly damaging the ceiling finish) it's usual to find a line of strutting fixed at right angles to the joists. Strutting also helps to ‘tighten up’ a floor, thus reducing ‘bounce’. The struts can form a herringbone pattern or can be ‘off-cuts’ of timber; usually staggered so that they can be easily nailed to the joists. |

|

|

The most complex part of the upper floor is the trimming around the openings. At Frederick Street the floor is trimmed around the stairs and around both chimney breasts. The construction around the chimney is design to prevent timbers catching fire. You can see from the left-hand graphic and the floor plan (top left) that there is a trimmer joist running parallel to the front of the hearth. This supports the trimmed joists, the trimmer itself is supported by the trimming joists. The hearth is usually supported by a half-barrel vault or brick infill. The photo on the right shows a similar detail on another late Victorian property (looking from below). |

|

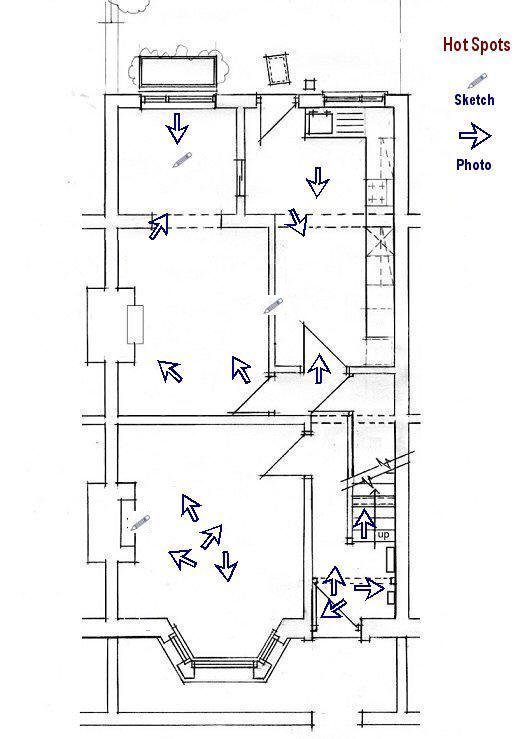

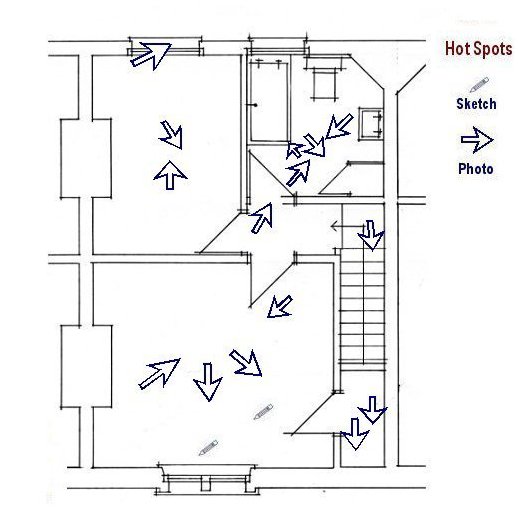

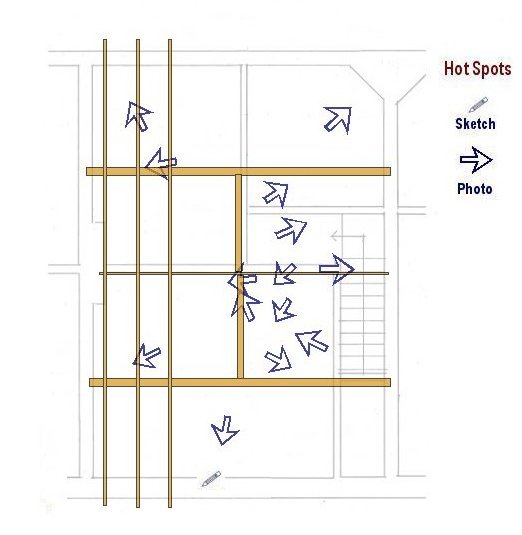

This page, and the next two pages, show floor and roof plans of Frederick Street. These are not to any particular scale and are included here to give some context for the reports. On each plan we have included two types of 'hot spot', some connected to sketches and some connected to photos. Try and familiarise yourself with the building layout before reading the reports. Click here to download a slightly more detailed drawing of the ground and first floor (pdf format). Click here to download a pdf of the five sections shown on the next two pages (pdfs of the hot spot sketches).

|

|

|

The following descriptions are those used by Allied Surveyors on their website:

A brief report in respect of value only which can be used for a variety of purposes including mortgage security, taxation, probate and family issues but does not constitute a survey.

This economy service for purchasers, devised by The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, involves a more detailed inspection and report than a valuation. It is generally considered suitable for modern, traditional properties and will include comment on all visible sections of the property, a market valuation and recommended reinstatement cost for insurance purposes.

This is the most detailed type of report available, and is particularly suitable for individual properties, including large, extended or older buildings. The report will include full details of all visible elements of the building and items of disrepair and defect. It will also include information relating to the method of construction, condition of the structure and likely future repairs. A recommended reinstatement cost for insurance purposes is included but the report does not include a valuation.

Source Allied Surveyors http://www.alliedsurveyors.com

Under sweeping changes contained within Part 5 of the Housing Act 2004, from mid-2006, sellers will be encouraged to obtain, voluntarily, a Home Condition Report (HCR) when they place their properties on the market. New legislation will mean that from early 2007 HCRs will become mandatory, as part of a Home Information Pack (HIP).

The HCR is the end product of considerable industry research and development and will not be a full building survey, but is a ‘level 2’ inspection and report. In other words it is intended to occupy the mid-ground between a market valuation type report (known as level 1), and a building survey (level 3). In some ways the HCR is therefore pitched at the same level as the RICS Homebuyer Survey and Valuation (HSV), except that does not contain a valuation. It is important to appreciate, however, that the HCR is not an HSV under another name, as new skills are required to fulfil the requirements of the new service.

Source:www.isurvlive.co.uk

Comments supplied by Robin Mewes, Residential Surveyor & Valuer, Allied Surveyors.

Clients are often confident that they can assess the condition of domestic property, or know someone that can help without involving professionals, so most homes are bought without a survey. Valuations (normally mortgage valuations) are more common and, as the value reflects the condition, act as a very concise and effective means of communication. The inclusion of a valuation in the HSV in a sense makes that report an extended valuation and explains why the HSV is more opinion based; the HSV and valuation are both overtly subjective.

If a client wants a report on condition with their valuation they should purchase an HSV and if they want just the valuation they should not expect a report on condition. This all needs to be made clear to the client at the outset to manage expectations and because HSVs represent such good value for money most purchasers enquiring will have an HSV rather than a valuation; most other clients (non-purchasers) don’t want or need a report on condition. The condition section of my valuation is therefore as brief as possible and simply conveys an overview as justification of value.

I would have charged between £150 and £200 plus VAT for the valuation on 32 Frederick Street.

Click here to view Valuation Report.

Click here to view Valuation office notes.

Comments supplied by Robin Mewes, Residential Surveyor & Valuer, Allied Surveyors.

It is normally perfectly possible to communicate all significant matters to a purchaser client using this report type, and at half the price (say £350 plus VAT) and with the bonus of a market valuation it is hardly surprising that this report has taken over from the Building Survey when dealing with the vast majority of ‘normal’ residential property. I find in practice that if commissioned to produce a Building Survey now I will be looking at some rambling and run down old farmhouse with outbuildings; a Listed house or certainly a house that is at least 100 years old. The HSV simply offers better value for money in most cases, especially when considering that most buyers only want to know whether the house and their purchase decision are sound. Purchasers are less interested in maintenance, so the extra information contained in a Building Survey is often only of real benefit after purchase.

While the HSV would almost certainly offer better value for money for the purchaser of 32 Frederick Street, the surveyor would have to work hard for the fee. The property has more than its fair share of issues and with hindsight the surveyor might regret charging a ‘normal’ HSV fee. There is always the option to walk away or re-negotiate, but that happens very rarely in practice. Assuming of course the surveyor is not out of their depth, they would normally crack on with the inspection; but it is essential that enough time is allowed to complete the job properly and the job should not be squeezed into a notional allocation of time to suit the surveyor’s fee rate. The client should be pleased with an HSV on 32 Frederick Street, but the surveyor may have been more gainfully employed elsewhere.

Click here to view the Home Buyer's Report.

Comments supplied by Robin Mewes, Residential Surveyor & Valuer, Allied Surveyors.

The most detailed report and consequently the most expensive. At a cost of say £700 (plus VAT) on 32 Frederick Street the client will want to see real advantage if choosing this report rather than an HSV. There were a number of faults at this property which, in hindsight, justify closer attention than that normally afforded through HSV inspection; but when discussing options with the client most of these would be unknown. In practice, faced with the prospect of surveying a normal but ‘scruffy’ late Victorian terraced house of modest size, I would recommend the Building Survey as the best report, but indicate to my client that most purchasers would normally have the less expensive HSV. It helps clients enormously if you talk over the basic differences, but they should also be referred to the guidance produced by the RICS and supplied with the detailed terms of engagement, before they decide.

Click here to view the Building Survey.

Click here to view site notes for the Building Survey (office file only - not for client).

Comments supplied by Robin Mewes, Residential Surveyor & Valuer, Allied Surveyors.

It is surprising just how different the HCR is from the HSV. It may just be my manner of writing, but my HSV style has more in common with that of the Building Survey in so far as it cites opinion. The HCR is more factual. It remains to be seen whether that makes the HCR a better report for the purchaser, but it should certainly make it more palatable for the seller. It is my experience that the seller will always disagree with my opinion, but be more inclined to feel well served if you point out a fact.

The fee, in practice, may be comparable with that of the HSV, but it remains to be seen what level the market will tolerate. The surveyor would have to accept that an HCR on 32 Frederick Street will take longer than average and ensure the inspection is not rushed.

There is no valuation in the HCR and often the valuation can take a great deal of time. With practice and as technology develops, the extra time taken to produce a more precise factual report should lessen and render, on average, HSVs and HCRs comparable in terms of time taken, but in this example comparable valuation evidence was readily available and the property was in poor order, so the HCR took substantially longer. On a time basis, in this example, the fee should have fallen mid-way between the HSV and Building Survey.

The property scores a lot of box 2s and box 3s; so the HCR clearly communicates the modest condition, so long as the client is familiar with the code.

Click here to view the Home Condition Report.

Click here to view the Home Energy Report.

Click here to view the Home Condition Report notes.

Building surveys call for in-depth professional and technical expertise if they are to be properly executed. Those who lack that expertise or have it but do not use it are liable if the job is done badly. The surveyor’s basic duty in common law is to exercise reasonable skill and care in providing advice. If this duty of care is breached the surveyor/valuer is laid open to a claim for damages in negligence. The standard is the same regardless of whether the individual is professionally qualified or unqualified. Therefore, a deviation from proper surveying practice may generate liability in negligence.

What are the standards of the average competent practitioner?

There are particular duties which are inherent in the surveyor’s job, which include:

How does the standard vary with the type of survey job?

The standard of care may depend upon the service agreed upon, for example, the elementary standard in the valuation report, compared with a medium standard of the Homebuyer Survey and Valuation (HSV) and the high standard in respect of a residential building survey. This is commonly known within the profession as the ‘Triple Option’ (levels 1, 2 and 3).

Valuations are required for many purposes, the most common being the residential mortgage valuation (commonly known as level 1) for an institutional lender, but also private buyers and sellers often separately commission such reports.

The case of Lloyd v Butler and another (1990) concerned a mortgage valuation where the valuer failed to reach the duty of care expected in such cases. It was concluded that the typical valuation inspection should last 20-30 minutes and requires ‘someone with a knowledgeable eye, experienced in practice who knows where to look ... to detect trouble or the potential form of trouble’. Although not necessarily obliged to follow up every trail of evidence, the case inferred that the valuer must alert the lender/borrower to the risk where serious defects are suspected and that further investigations should be made before there is a legal commitment made to purchase.

If there are no clearly identifiable signs of suspected problems, or a surveyor misses defects because the signs are hidden or concealed, then it will be difficult to demonstrate negligence. This was one of the conclusions in Smith v Bush (1987).

Ninety per cent of individuals buying property rely entirely upon a lender’s valuation.

Effectively falling between a mortgage valuation and a building survey, the HSV (commonly known as level 2) is a form of limited contract which tightly defines the extent of inspection within its terms of engagement.

The HSV provides a standard pro forma report using headings covering structural elements and ‘urgent’ and/or ‘significant’ defects. This replaced the HBSV (Home Buyers Survey and Valuation) in 1997, which in turn replaced the former HBR (House or Flat Buyers Report) in 1993.

A high proportion of the problems that arise on this type of survey are simply because the parties are not sufficiently clear about the nature and scope of the survey. The client’s expectation is usually that the HSV is effectively the same as a building survey.

The amount of time spent on site is typically 90 minutes (SAVA HSV Benchmarking). There are no restrictions on the type of property that must be inspected under this scheme. This changed previous guidance which limited the scope to include only properties of standard construction built after 1800 with less than 2000 sq ft gross floor area.

A residential building survey (commonly known as level 3) is intended to provide the buyer with the most extensive (and therefore the most expensive) report option. The inspection and report is limited to readily accessible parts of the property, and so unless the client makes specific arrangements with the owner to lift or move furniture, lift floor coverings and take up floorboards, the surveyor will not generally be expected to do so. The surveyor will not normally test the services, but may be instructed to coordinate electricians, heating engineers, etc. The precise extent of liability will depend upon the precise terms and conditions of engagement that the surveyor and client enter into.

The case of Hacker v Thomas Deal and Company (1991) involved a building survey (known then as a structural survey). The judge stated:

‘Bearing in mind that there is a difference between the various types of reports which are produced upon the sale and purchase of houses, and in particular, that this was not a valuation report but a structural survey ... which involves a detailed and thorough inspection of the property to be inspected ... it obviously involves seeing what there is to be seen through the eyes not of the layman but of the expert.’

The surveyor in this case was likened to a detective trying to anticipate problems, and to visualise what could be happening within the areas of the building which are inaccessible to the naked eye, but without actually disrupting the fabric, decorations or the fittings of the house. The judge went on to say that in this situation ‘one does not start going into all the little crevices in the hope of finding something unless there is some tell-tale sign which indicates that it would be advisable to do so’.

The courts clearly expect a greater standard of inspection, and a deeper knowledge and expertise is demanded in the case of building surveys compared to HSVs or valuations. Clients therefore appear to get what they pay for when it comes to the surveyor’s exposure to liability.

Although the role of ‘Licensed Home Inspector’ does not yet exist, and legal precedents have not yet been established, parallels can be drawn with the work of chartered surveyors engaged in carrying out surveys of residential properties.

What are the standards required to work as a Home Inspector?

The standards required to undertake home inspections under the proposed legislation, are contained in the National Occupational Standards for Home Inspectors. The standards have recently been approved by the Qualification and Curriculum Authority and they state that a Home Inspector will have skills and competence in:

The reforms are still in the process of development and changes to the detail of some of the proposals will undoubtedly take place before the final stages of implementation. Further information may be found by visiting the following websites:

Office of the Deputy Prime Minister:

see the page on the Home Information Pack

www.odpm.gov.uk/stellent/groups/odpm_housing/documents/divisionhomepage/033116.hcsp

see also ODPM Factsheet 7: The Home Information Pack available on

www.odpm.gov.uk/stellent/groups/odpm_housing/documents/page/odpm_house_030196.hcsp

The HICB Steering Group: www.thehicb.org.uk

Asset Skills: www.assetskills.org

Property Information Research Ltd: www.pirltd.org.uk

Quite distinct from the professional issues that may generate a negligence claim there are situations in which bad advice is given because of poor quality control or failure to follow very basic routines. The problem areas include:

Increasingly, professional indemnity insurers are beginning to consider the following information prior to assessing relative risk and levels of premium for individual firms of surveyors:

Surveyors are typically open to an action in negligence when they fail to:

Source: www.isurvlive.co.uk

This page has been supplied by Robin Mewes (who carried out all the above surveys) and is a very brief introduction to Allied Surveyors.

Allied Surveyors is the trading

name of Allied Surveyors plc and Allied Surveyors Scotland plc. It is an

independent company of Chartered Surveyors with offices throughout the UK.

Their teams of experienced Chartered Surveyors provide professional property

advice to major lending institutions, companies and private individuals.

They have been appointed to most of the panels of mortgage lenders enabling us

to undertake a simultaneous detailed survey inspection of property for private

clients.

They have ISO 9001:2000 Quality Assurance accreditation.

Allied Surveyors was formed in 1991 by bringing together eight established practices across the South of England. They have expanded by inviting other reputable firms to merge their survey and valuation departments with Allied Surveyors. The company therefore has some 70 associated businesses that also offer other services including Estate Agencies in many locations.

For details please visit www.alliedsurveyors.com

©2006 University of the West of England, Bristol

except where acknowledged