32 Frederick Street

6 Construction - Main Roof

|

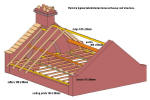

The main roof of 32 Frederick Street is a purlin roof. Until the 1950s, this was the most common type of roof construction in the UK and, in the from shown here, is ideal for small terraced, or semi-detached, houses. The roof comprises a series of sloping timbers known as rafters, supported at the bottom by a wall plate, and at the top by a ridge board. The rafters are usually 75, 100 or 125 x 50mm, depending on span; they are usually fixed at 400mm centres (16 inches). Ceiling joists support the ceiling and prevent the feet of the rafters from spreading. The roof stays in position because it's heavy (several tonnes when tiled). The roof is covered with Double Roman tiles. A series of lead (maybe zinc) soakers seal the junction against the parapet party walls. |

|

|

The ridge board helps maintain the rafters in the correct position as the roof is being built. Once the roof is complete it becomes less significant in terms of the roof's stability and rigidity. It's usually built into the gable ends, sometimes supported on corbels. At the eaves the rafters are normally notched over a wall plate bedded on top of the external walls. The ceiling ties should be well secured to the rafter feet. The insulation should run into the eaves (to prevent cold bridging around the edges of the ceiling) but should not block any ventilation. |

|

|

To help keep the rafters to a sensible size they are usually supported mid-span by a purlin. In theory it's possible to increase the span of a roof and prevent deflection by using ever increasing rafter sizes. However, the use of very deep sections is both uneconomic and also creates handling problems on site due to their weight - a purlin is therefore more practical and cheaper. A purlin is a large timber beam which generally supports the rafters mid span thus preventing deflection. The purlin spans from party wall to party wall and, besides supporting the rafters, provides lateral stability to the gable end walls (i.e. at each end of the terrace or in semi-detached and fully-detached houses)). It's usually built into the gable or party walls and, again, can also be supported on corbels. A 3D model of the whole roof at Frederick St is shown on the left. |

|

|

In very small terraced houses the purlins can easily span from party wall to party wall. However, as the width of a property increases so must the depth of the purlin if it is to be strong enough to take the load imposed on it without undue deflection. Very deep purlins, say over 250mm are expensive, difficult to obtain and difficult to handle on site. In practice it's more economic to use smaller purlins and provide intermediate support in the form of struts, built off internal loadbearing walls. In a terraced house the size of Frederick St you will normally find one pair of struts, bearing on the wall between the two main bedrooms. The struts at Frederick St are so shallow, they are almost ineffective. |

|

|

Where there is no means of supporting struts,

some other means has to be found of supporting the purlins mid span. In

larger roofs this is traditionally done by a heavy truss (left). You won't

find these in small terraced houses.

The ceiling joists which span from plate to plate are often of smaller section than rafters, and to prevent them sagging in the middle some form of intermediate support is often provided. One method is to secure the ceiling joists with a horizontal member, called a binder, and to hang the binder from the ridge. An alternative, of course, is to use joists of increased depth but this is usually a more expensive solution. At Frederick Street the joists are supported by the external walls, the internal wall between the two bedrooms, and a pair of binders. The photo (left and above) shows a binder running below the purlin. The photo on the right shows that hangers and binders are still used today, even though most roofs are built with prefabricated trussed rafters. |

|

|

In the roof void there are two main things of interest, the 'gathered' flues

(left) and the two cold water cisterns (right). The larger cistern feeds the

hot water cylinder and the smaller one the boiler - the cold water

supply is direct.

There are four fireplaces on the party wall, each served by its own flue. These are gathered into a single chimney (with four pots -8 including next door). The construction is quite complicated and there are a number of defects to look for. These are explained in much more detail on the Construction Web Site (Heating section). |

|

except where acknowledged